JeremiahBishop.com

The Official Website of Jeremiah Bishop: Professional Mountain Bike Racer, Canyon Ambassador, and Cycling Coach

Opportunity for Adventure

While there are no races or group rides, now is a huge adventure opportunity. A time to dust off old routes and fill the bucket list with new ones!

On May 31, at 5:53 a.m. I set out to take on The Kracken. I knew this was really pushing the limit. The idea of doing a 200-mile Dirty Kanza tribute ride sounded awesome: I could get deep into the ultra-endurance zone and earn that post-ride crushed feeling without driving to Kansas.

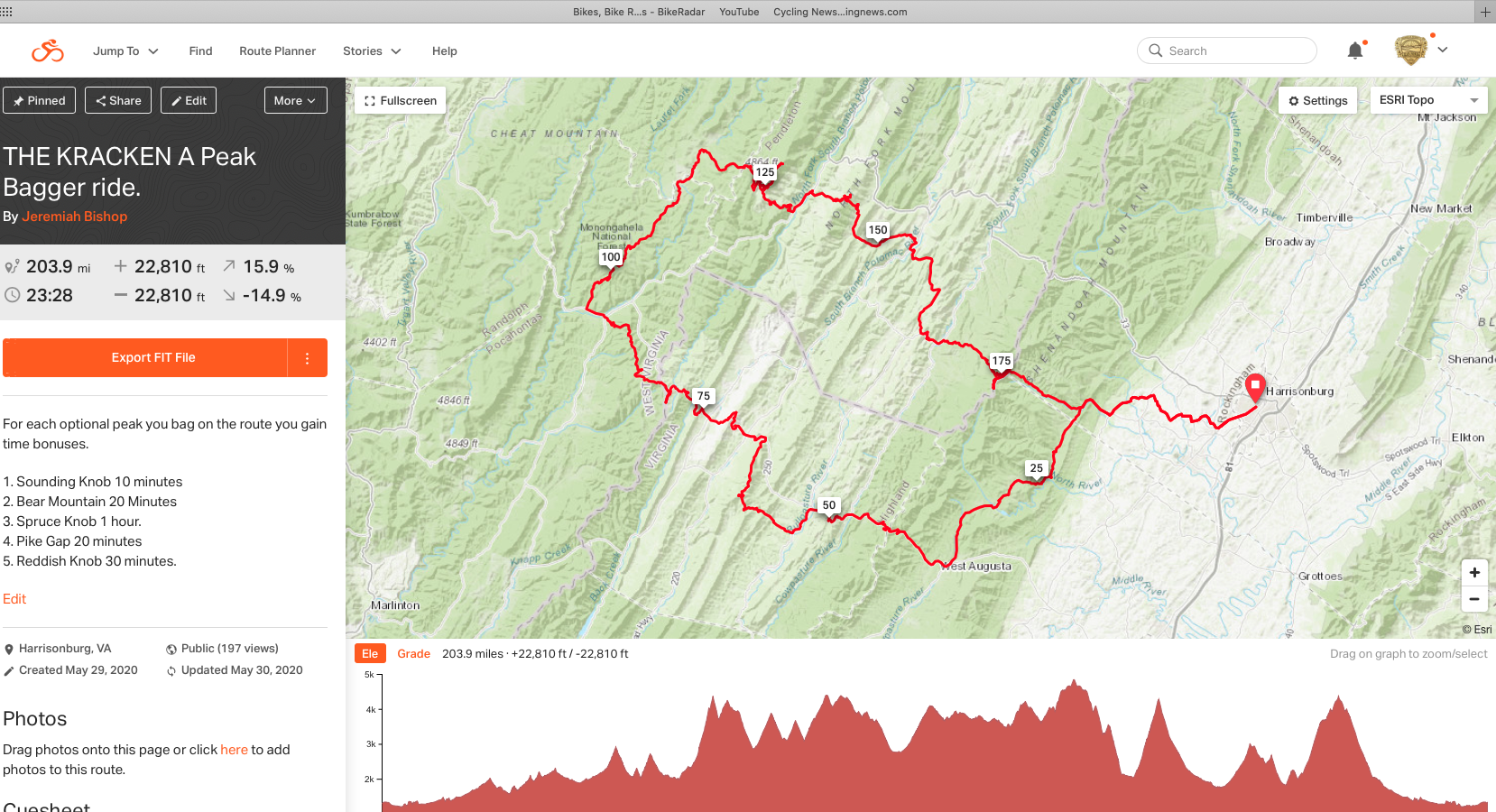

I looked through the 190 routes I’ve created on Ride With GPS and Strava. One called to me. Buried deep in the back of the archives, there lurked The Kracken. It was not only the hardest of my gravel routes, but it was chock full of new-to-me mountains. The Kracken climbs 22,810 feet in 204 miles. ‘That’s the one!’ I was beyond stoked! Also, a bit nervous.

This tour-de-pain features some of the highest mountains in West Virginia. It travels past civil war sites and old lookout towers the US Forest Service used to watch for wild fires.

My love for big gravel has grown as the bikes have become more refined. The new Canyon Grail and Endurace make this adventure stuff so much fun to take on.

This crazy route had everything: valley farm sunrise, super remote gnarly mountain passes, and windswept open mountaintop vistas! I took off at exactly sunrise. I crossed the rolling gravel of the Shenandoah Valley in the crisp morning air. My route threaded through the mountains on some warmup climbs in the George Washington National Forest. I crossed into West Virginia, climbing up serpentine switch backs. The ascent of Sounding Knob, my first big test, was very remote. It started by crossing some cold, fern-lined streams. The climb was much harder than I thought it would be, especially with all the food for my day’s adventure loading me down. I had PB&J’s, some fruit twist treats, some oatmeal cream pies, and

of course, Mountain Dew the unofficial state drink of West Virginia. In addition to all the food, I had a water filter, tools, and a backup battery.

I hit the big bald expanse of the 4,400-foot Bear Mountain. The 360- degree view was outstanding! I descended toward Bartow, the only village I’d see for hours. I started steadily climbing up Brurner Mountain’s many gravel switchbacks. As I approached the turn to climb to the highest point in West Virginia (Spruce Knob) I was well in ultra-zone; 10 hours in, about 70% through the route, a bit dazed mentally, but moving good toward the top. Unfortunately, some sharp rock with an agenda had other plans for me.

On rides this over-the-top there is always an unexpected challenge.

I suffered the worse kind of flat: a cut side wall. I had numerous tire plugs, two tubes, and a pump. I’d expected at least one flat along the way, and was prepared for more. The first fix worked, but the plug was rubbing the frame and I had no razor or knife to trim it with. I accidentally pulled it trying to cut it with my Mountain Dew can, making the hole worse. I had to tube it. This worked, but only for a half and hour of tender progress. I was in the middle of nowhere in the deepest forest you can imagine. I was late to the planned meeting point at Spruce Knob. Luckily, I ended up making it an hour to the pavement before riding some rim.

I tried to call my wife Erin who was ready to assist, but this area is in the National Radio Quiet Zone for the huge radio observatory in Green Bank. I literally had no cell signal for 100 miles. If you put a radio on search mode, it just circles through the stations on infinite repeat finding nothing. Erin and our kids had had driven from our house to Spruce Knob, where we’d planned to meet. Then they searched for me on the gravel road ascent. Eventually she decided to drive home, hopeful that I’d cut the route short and would be on the Virginia side of Shenandoah Mountain. Finally, I made it to Franklin, West Virginia where there is cell service and we were able to connect. I sat there, despondent on the side of the road. I was lucky they

came back and rescued me.

The Kracken did succeed in having me in the box and rewarded like Kanza. And I forged a keeper route that is super rad.

capability versus challenge.

This mission was more than I should have taken on, given the circumstances. It relied on things going perfect, or at least as-planned. I’d not properly considered that adventures this ambitious never go as planned.

Would I do it again? Hell, yeah. But I would prepare like it’s a bike-packing trip through Alaska.

Lessons learned:

When picking an adventure, you must create a solid plan. Part of this is by assessing capability versus the challenge. Secondly, you must factor in uncertainty and how that create a risk multiplier of the unknown. Lastly, have a solid emergency plan with some built-in redundancies. Admittedly, I had some additional back-ups built into my plan, but in my exhaustion I didn’t follow through with them.

I have solid fitness, a great bike, and I knew it was a low-traffic route. Normally I’d sign it a moderate risk level, but the 200+ miles pushed into a more likely for high-risk adventure. Looking back, the lack of cell phone service, plus the untested route, plus the pandemic-effect of not being able to jump in a car with a stranger for ride was the final thing that put my plan into the might-be-a-bad-idea RED Zone.

My plan had holes in it.

Will I do it again? Definitely. After I apply the lessons learned:

#1 Don’t mess with The Kracken. Understand it’s not a bike ride, but an expedition.

#2 Ride with a satellite phone or Spot Tracker. Get a prepaid phone SD card for all other carriers.

#3 Bring a spare tire!

At 2,656 square miles, Monogohala National Forest is big, and super awesome.

P.S. In a couple of days, I will finish the un-ridden portion of the route to see how the rest of it rolls.

Latest “In the Wheelhouse”

Adventure starts when things go wrong, right?

“The Ring” FKT

The Legend

What started as a fun local challenge, turned into a game, and that turned into a personal battle for me.

The 70-mile ultra-rocky Massanutten Trail, also known as “The Ring,” circumnavigates the high mountain ridge that surrounds historic Fort Valley in Northern Virginia. This trail has slowly become the stuff of legends. Year after year riders make their attempts and often fail to complete The Ring because of fatigue, mechanicals, and all types of other conditions.

Less often, a few intrepid souls succeed. Because of the rocky and unrelentingly technical nature of the trail, over the years the fastest known time (FKT) of The Ring has only crept toward the 20+year foot running race record held by Paul Jacobs of 13:29. It was not until October of 2019 that mark was breached by rock riding legend and trail builder Sam “Skids” Skidmore. He became the first mountain biker to surpass the running record with a time of 12:22.

My Early Attempts

Fall 2008

My first round in The Ring came after a busy race season. In those days, autumn seemed to be the only time that would for work for this type of endeavor; the risks are season-ending level dangerous. That year, my friend Sam Koerber and I encountered rain and pain, crashes and fatigue. I remember fumbling on some rocks and dismounting. I put my foot between two rocks at shin level and fell. I could imagine my bone sticking out when I looked down, but it was just a cut. My sock being filled with blood was just one of many distractions. November’s short days and terrible conditions made a strategic retreat for more favorable days seem logical, even though demoralizing.

2018

It took a few years before the call of The Ring once again beckoned. I got older and wiser. I had moved on from World Cup XC racing to ultra-endurance and stage racing. My love of rocky riding stayed with me. Thoughts of the whispering wind on pine strewn ridge tops, near-perfect sandstone, and raw magical riding enchanted my imagination. I told myself I’d head back to The Ring after a busy round-the-world race season with Canyon-Topeak. The eventful season wound down. Stoked with confidence from major race wins, I thought I was ready. Then just 5 hours into my effort I found myself struggling. I caught a stump with my rear derailleur. The mishap destroyed my derailleur hanger and took some spokes with it. That attempt was over.

2019

The spring of 2019 looked like the next promising time to come back to The Ring, until the combination of a late-fall back injury and an early-spring knee injury proved to make the Cross Fit-type efforts I would need to produce impossible. I had to face the fact that at 43-years-old my window to complete The Ring seemed to be closing. At times I had thoughts like ‘I’m getting too old for this shit.’ My body might not be able to do this extreme of an effort anymore…. Do I want to take the risks needed to nail this one at race pace?

2020 An Unexpected Opportunity

This is it, I thought. Through the winter, I trained relentlessly. I had a good build up; hitting the gym, running, doing plyometrics, and all-day hammer rides. And a return to rocks.

In February, I summited Mauna Kea in the first ascent of “The Impossible Route.” Nothing can stop me this time, I thought.

Then the world changed. News headlines turned into life-altering realities. “Lockdown… Schools Closed… Unprecedented Modern Pandemic… COVID-19 Death Toll Set to Reach Hundreds of Thousands.”

My plans froze in their tracks, as did most. Everything shifted into emergency mode. We prepared. We stayed home. My Ring plan seemed doomed yet again.

Then, after 3 weeks of training at home in the new bizarre quarantine world, there was a bit of calm and I realized this is the time. No one in our immediate family fell ill thankfully, and I sensed this was the time. I decided the coronavirus pandemic was not in my way unless I let it distract me. I could focus on the pure effort of The Ring without the normal routine of the race-travel season. The call of adventure was strong and the need to do it while my body could was the overwhelming decider. My goal was to minimize risk and focus on a smooth run. I planned to make an attempt the second week of May.

In the weeks that followed, I did what many cyclists in the U.S. were doing – virtual training rides from home and solo training rides outdoors. My neighbor Abe Kaufman and I traded Strava times on the local training route known as “The Mini Ring.” I sharpened my rock game and I got my rock groove back a bit as we traded leads. I was not as good as I used to be, but very close.

Then one day as I was preparing my gear, a notification came through on Strava – likely informing me that I’d lost some random KOM segment. I opened the notification to see that Abe had set a new all-time FKT on The Ring! I almost spit my coffee out! What?! Abe had just pushed the record deeper into the end-zone. An astonishing 11:52! This jab to the chin helped me push aside the fears of what if. The trepidation of going that hard for full cycle of the wall clock was going to hurt a bit, but I just said I’m going to enjoy it and drive it.

In the following days, I chatted with Abe and congratulated him on a stellar mark. He gave me minimal advice but stated flatly, “Remember: slow is smooth, smooth is fast.”

This was a riddle that had my mind in a loop, but I took it to mean ‘don’t crash or wreck your bike, because it will save you an hour or just allow you to finish the damn thing for once.’

I decided I was going to drill it smooth and steady; see what happens. I wrote the phrase on my stem as if the mantra might protect me from evil spirits. “Slow is smooth, smooth is fast.”

My Day Had Come

The weather forecast showed an unusual cold front was approaching that would bring perfect dry cool conditions mid week. I was gifted a cool dry day with a lot of daylight. My new Canyon Neuron had me more confident than ever on the slabs of steep serpentine trail.

On May 13, I set off on the Massanutten Trail just after dawn.

Check Point #1: Kennedys Peak

Thus far, my rock game was a C+ at best, but I was able to press hard on the rhythm sections and fought to gain back time I’d lost on the super-technical stuff. I refueled and dropped my pack. I looked at the clock. I was actually 20 minutes ahead of pace somehow with an average speed of 6.5 mph. I needed to do the whole thing faster than 6.4mph to break the mark.

Checkpoint #2: Waterfall Trail

Legs cramping I hiked for 30 minutes on this brutal wall of a pitch. I slipped walking and smashed my anklebone so hard on the rear skewer it made a whack sound. Nerve pain shot up my leg. I gasped. It felt like everything was trying to stop me. I was suffering now. Sweat burned my eyes and my arms were so tired it took both hands to hoist the bike up only for me to fall to the ground more than once. But this is what I came for, I reminded myself. I was losing time fast. Now time with the record speed of 6.4mph I was worried.

Checkpoint #3: Jawbone

This is the most brutal and rhythm-challenging section with ample hike-a-bikes, sketchy rock piles, and relentless chances to crash and land on jagged rocks shaped like broken pieces of concrete. I went over the bars on one steep drop-in, smashing my thumb into a crevasse between the rocks. Bike was ok, but I thought my thumb could be fractured. I assessed the damage as acceptable and kept moving. After taking that hit, I was below pace now; 6.2mph and dropping.

Checkpoint #4: Short Mountain

This segment demands the biggest rock moves of the route and I consider it the crux of The Ring. Here you will either fall apart or make up time. Up to this point, you’ll have faced many exhausting hours of wrestling to burst up steep staircases of rock and dropping in hard, fully braced for each obstacle. If you get this far, you get here just crushed. I was coming apart. My hands raw, my neck tight, and my quads weakening, I started running into trees and rode clean off the trial at one point. Something’s wrong, I thought. My speed was now off pace. ‘No FKT today,’ I resigned, but I just have to finish. I will finish. I stopped for a refuel and tried to compensate for the dehydration that was sabotaging my focus and my energy.

I stared down the nasty hiking ascent of Wonazi Peak with a “can do” attitude. I was getting my hydration under control and was actually feeling some strength coming back. Then I stuffed my front wheel into a brick-shaped rock; it stopping my bike. This sent my knee full-force into the stem. I cursed for the first time of the day. I looked at my stem and took a deep breath. “Slow is smooth, smooth is fast.”

I went back to foot-mode for the 300th time. I was slipping on the rocks now as I walked, rubber almost gone from my shoes. I was about 20 minutes off pace.

Checkpoint #5: Woodstock Tower

West Ridge is the fastest section of The Ring. It’s a little bit downhill and drops 500 feet gradually. ‘Maybe I can make up some time,’ I thought. I will try one last time to get on terms with record pace. I pushed into cross-country mode. I was driving turns and pushing out of the saddle. Focus. Focus. Finding a rhythm to the rocks, I was coming back on line. Goose bumps. I might still have a chance.

At Woodstock Tower I was only 12 minutes behind pace. Now my effort was showing gains. I pushed harder into the red. Food was mostly gone; I expected to run out with about 1 hour left. My energy was holding at 70-percent, but was steady. On a steep climb I miss-shifted and stopped to see the problem: one 1/4th of a ring of the cassette was broken off. I gasped, ‘no, no, NO!’ I came this far I can’t lose it now. I turned off the Black Eyed Peas music in my earbuds. Riding super technical rocks and counting what gear I was in took 100% concentration; one mistake and I would shear the rear derailleur off or break the chain.

Checkpoint #6: Mud Hole Gap

Within a couple minutes of record pace I ripped the descent in a flash. I was tied with record pace, but hydration was still a struggle – too much sports drink plus food left me so thirsty! I saw a small trickle of a steam draining cold water down the side of a ditch. I stopped. I had to drink it even though this would cost me time. Bright green moss from where the trickle started from a big rock seemed like a good spot. I dug a small hole in the sandy dirt with my hand to scoop up a half bottle of cold clear water. It tasted amazing and was invigorating. ‘If it makes me sick, it wouldn’t hit me until after the ride,’ I thought and I moved on. Slow is smooth. Smooth is fast.

I hit the technical ridge top of Signal Knob. It was more technical than I remembered, but also I was riding sections of it I had not cleared 12 years ago and on a lesser bike. Now the Canyon Neuron and my body found some equilibrium and balance. I was in a good mode, and really enjoy the low light playing through the trees, only half- dressed in their spring leaves. I walked a couple nasty spots and was smooth and efficient, knowing any high-risk mistake now would be just greedy and foolish. Slow is smooth, smooth is fast.

I arrived at the finish of Signal Knob Parking Lot, forearms pumped and barely able to hold the bars from the final 20 minutes of descending. I was reluctant to look, but the clock stopped at 11 hours, 36 minutes. ‘Got it.’ I just fell over into the gravel and took a deep breath. Relief is all I felt.

It was like being up all night fighting a bear that had been stalking me. It would reemerge from the dark again and again. Finally I killed the bear. I was super happy, just glad I survived I cracked a smile for the camera.

Making Sense of It

The day afterward I could barley walk, my hands were ground-beef red. I was bruised, scratched by briers. I felt like I had been in a car wreck and aching all over.

Two days later I did a Technicolor spin through the countryside on my Grail. That’s when it really started to sink in. I felt like I’d eaten a pound of skittles! ‘YEAH! I did it,’ I screamed out at the top of my lungs! How in the hell did I do that, I thought? That was freaking awesome! I nailed it down and overcame the doubts; anything in the world seems possible now.

I am not the FKT owner of The Ring, rather I now own the freedom from the burden of unfinished business. The Ring no longer owns me. Now I can just enjoy riding those rocks.

Jeremiah BISHOP-CANYON Virtual Schedule

With a full virtual schedule lined up, you can join Jeremiah for a ride on Zwift! All times below are Eastern. This page will continue to be updated with upcoming virtual events. Follow @Jeremiah BISHOP[CANYON]3771 on the Zwift Companion App for ride invites, when applicable.

Monday 6:15 AM

Monday Morning Blues Zone 2 Zwift Ride with DIRT Zwift Team

Every Tuesday 8-8:30 AM

JB’s Canyon Cafe Facebook Live Q&A Coffee and Bishop Training Chat

Follow Jeremiah Bishop on Facebook or watch live from JeremiahBishop.com Facebook insert below.

Weekly virtual events will continue to be updated!

The Impossible Route

The Impossible Route is a cycling documentary that tells the story of Jeremiah Bishop and The Vegan Cyclist as they ride bikes up the world’s biggest mountain – the Hawaiian volcano Mauna Kea. Mauna Kea is the world’s largest volcano and has objectively the world’s hardest road climb up to its summit. The Impossible Route chronicles the duo’s attempt at the first ascent of the gravel cycling route from sea to summit.